Bone Stress Injury / Fracture : A Comprehensive Rehab Guide!

Have you recently been diagnosed with a bone stress injury? This article discusses the research surrounding bone stress injuries, optimal management strategies and how to successfully navigate the return to running / sport process. Click on the links below to navigate to the relevant section :

What is a Bone Stress Injury?

Why Do They Occur?

The Bone Stress Injury Continuum

Common Injuries & Symptoms

Low Risk v High Risk Fractures

Diagnosis & MRI Classification

Risk Factor Identification & Management

The 5 Phases of Rehabilitation

A Return To Running Plan

When Can I Start Running?

Pain & Running Following a BSI

Conclusion

Bone Stress Injury in Runners

A bone stress injury (BSI) occurs in response to chronic repetitive stress, leading to an imbalance between bone formation and bone resorption (Nattiv et al, 2013). The strength of the bone is then compromised, making it more susceptible to injury. This can then lead to the bone being unable to tolerate repetitive mechanical loading (e.g. running), with symptoms of local bone tenderness, pain and swelling commonly experienced (Warden, Davis & Fredericson, 2014).

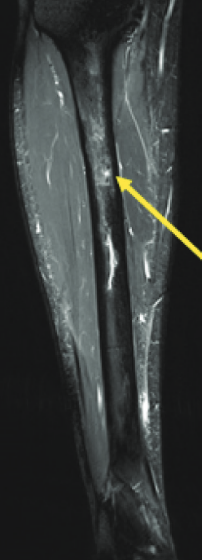

T2-Weighted MRI of a Fredericson Grade 3 bone stress injury of the tibia. The arrow demonstrate marrow oedema. (Nussbaum et al, 2022)

Why Do Bone Stress Injuries Occur?

Multiple factors are usually at play that contribute to the development of a bone stress injury. Addressing the factors relevant to you is key during rehabilitation. Some of these factors are outlined below.

BSIs are prevalent in female distance runners. The incidence of BSI has been reported to be 2.25 times greater in oligo / amenorrhoeic (irregular / long menstral cycle) than eumenorrhoeic (healthy menstrual cycle) runners (Hutson et al, 2021). The authors suggest that in order to reduce the risk of BSI, female distance runner's should monitor their menstrual cycle, and avoid prolonged periods of low energy availability.

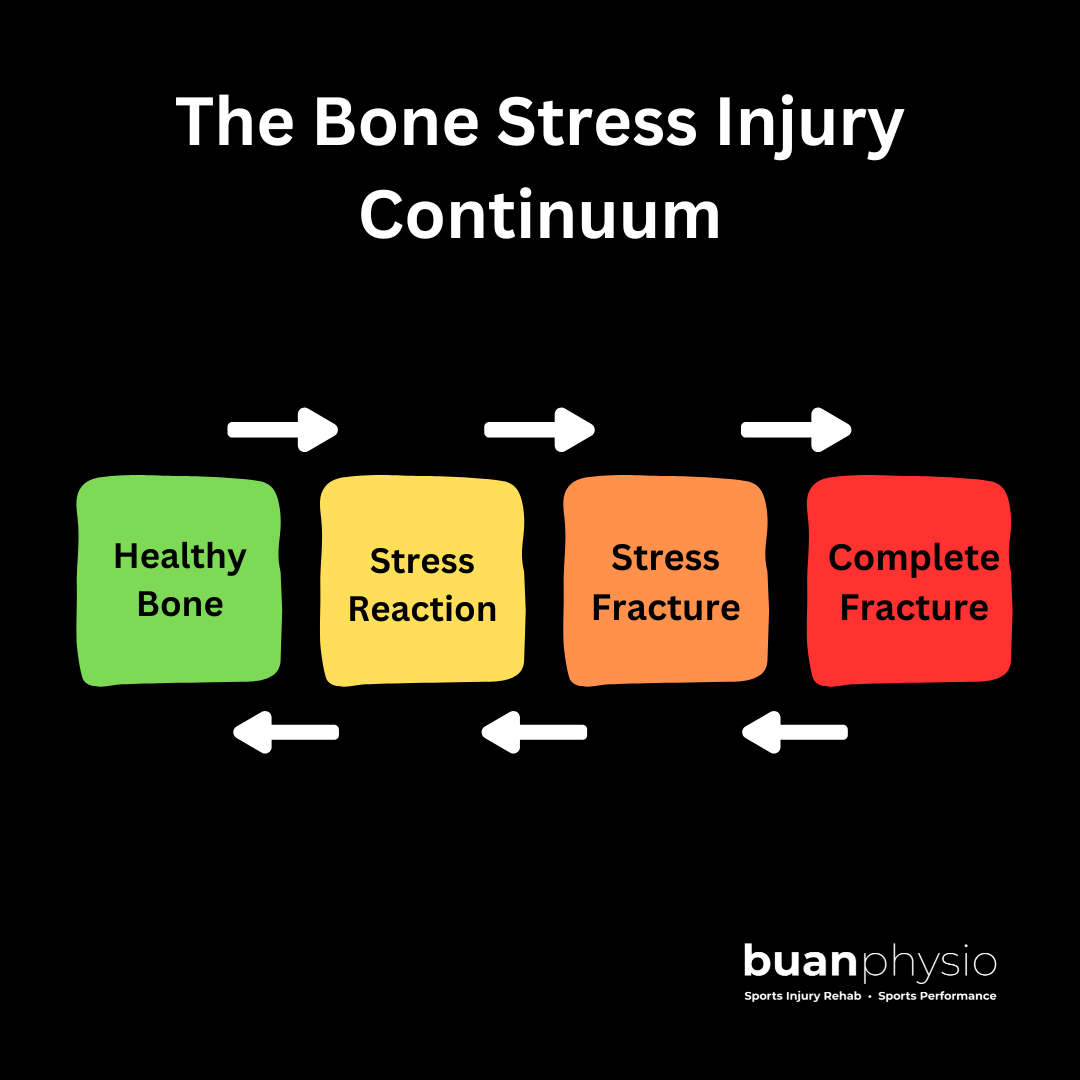

The Bone Stress Injury Continuum

BSI's are related to training load errors, and they occur along a continuum that begins with a stress reaction. If not managed appropriately, this stress reaction can progress to a stress fracture, and then a complete bone fracture (Warden, Davis & Fredericson, 2014).

Early recognition of the signs and symptoms of a bone stress injury will prevent an athlete from ending up on the the right hand side of this continuum (Image, Buan Physio)

Common Bone Stress Injuries & Symptoms

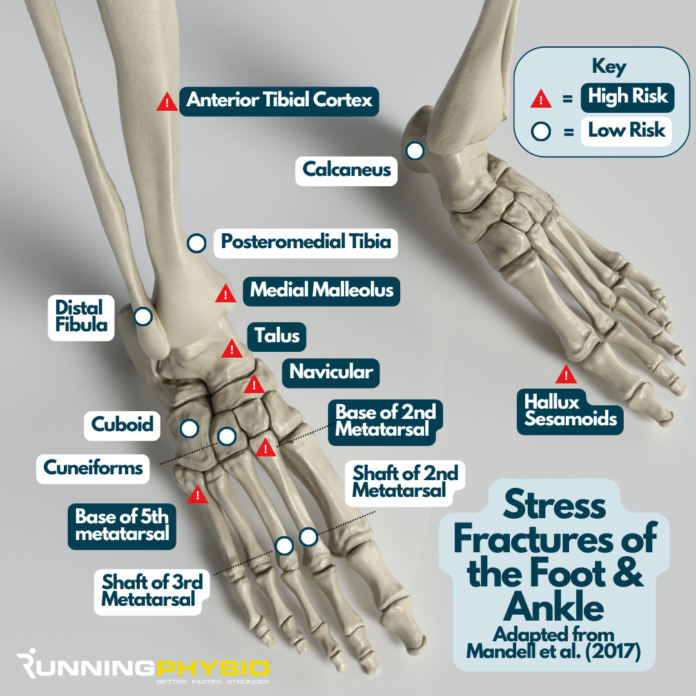

Image from : https://www.running-physio.com/stress-fracture-graphic/. Adapted from Mandell et al (2017)

Both adult and adolescent long-distance runners along with team-sport athletes, can suffer bone injuries. Stress fractures to the tibia (shin) and metatarsal (foot) are commonly diagnosed. Low-risk bone stress injuries (BSIs) are typically found in the compressive regions of the tibial and metatarsal shafts, specifically on the posterior cortex of the tibia and the dorsal cortex of the metatarsal (Derrick et al, 2016). Distance runners have some of the highest incidences of BSIs, with low bone density and relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) often being contributing factors.

"Another important contributing factor is that distance running simply is not a good bone building activity" (Warden, Edwards & Willy, 2022)

This is due to bone cells becoming desensitised to repetitive straight-line running loads. However, a phase of relative rest does allow the system to recover its mechanosensitivity, facilitating further adaptation (Warden, Edwards & Willy, 2022). Bone adaptation to loading occurs in alignment with the direction of the applied load (Warden et al, 2020).

Therefore, athletes that are involved in uni-directional sports (e.g. distance running) would benefit from including multi-directional bone loading activities in their programming. This could include jumping, hopping, bounding and landing exercises.

The incidence of bone stress injuries (BSIs) in females and males across collegiate sports in the United States over a 10-year period. N/A = data not available. Data from Rizzone et al, 2017. Table from Warden, Edwards & Willy, 2022

The symptoms experienced with bone stress injuries can vary between individuals, however the list below outlines the most common symptoms to look our for :

Pain that increases the longer you run

Pain that is worse after the run and the following day (causing a limp)

Pain at rest (e.g. night time pain)

Localised bone tenderness

Focal swelling

Low Risk v High Risk Stress Fractures

Buan Physio Image. Adapted from Robertson & Wood (2017)

BSIs can be classified as either low risk fractures or high risk fractures. Bone healing timeframes and recovery duration are influenced by which category your injury falls into. For example a low risk fracture will often heal well with adequate rest. Whereas there is the potential for non-union or delayed union when dealing with a high risk BSI. Surgery may be indicated for some high risk BSIs. The image above outlines the most common low and high risk BSIs.

Diagnosis & MRI Classification

MRI is the most sensitive and specific imaging modality for identifying bone stress injuries. However, the decision on whether to refer an individual for an MRI should be based on various factors, including : their mechanism of injury, running loads, objective test findings (e.g. bone tenderness, positive special tests) and the presence of BSI risk factors (e.g. previous BSI). Various objective tests exist that can help to identify the presence of a BSI, but these are never used in isolation when forming a differential diagnosis list. Some common objective tests are outlined in the table below.

“When an individual exhibits high running loads, along with risk factors and bone tenderness, and additionally shows an inability to 1-leg hop (or experiences pain while hopping), they should be considered as having a bone stress injury (BSI) until proven otherwise.”

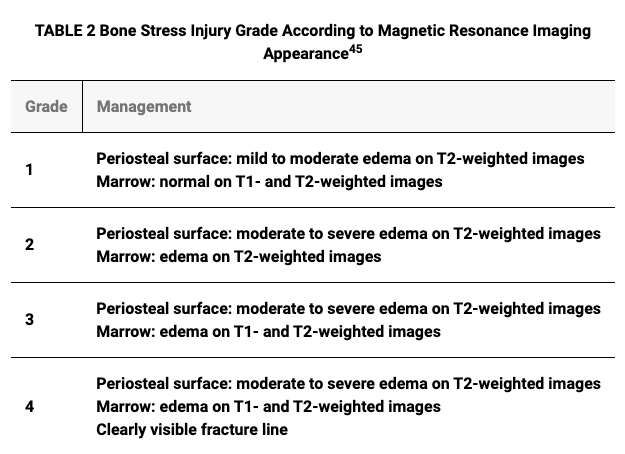

Various MRI classification systems exist for examining the severity of BSIs. Fredericson et al (1995) developed a a four-grade classification system for investigating tibial BSIs, which can be seen in the table below.

Grade 1 and 2 BSIs on the grading system can be grouped as low-grade BSIs, whereas grades 3 and 4 can be categorized as high-grade (Chen, Tenforde & Fredericson, 2013)

However, in a study by Kijowski et al (2012) aimed at validating Fredericson's system for tibial stress injuries, the authors found that grades 2, 3, and 4a stress injuries had similar degrees of periosteal and bone marrow oedema, along with similar return to sport timeframes. Therefore, they suggested that these three grades be combined into a single category (Grade 2 below). The abbreviated Fredericson classification system for tibial stress injuries is outlined in the table below.

The abbreviated Fredericson classification system for tibial stress injuries (Kijowski et al, 2012).

The 5 Phases of Rehab

Rehabilitation from a bone stress injury involves 5 distinct phases.

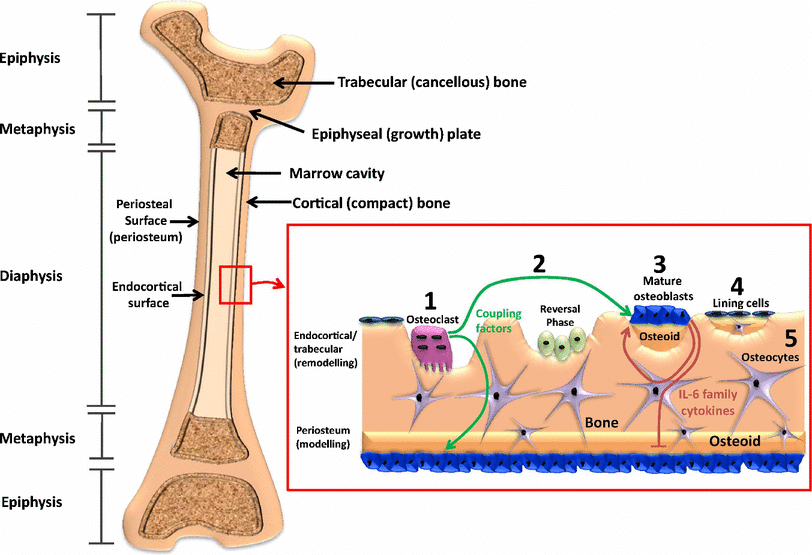

To provide the optimal conditions for healing to occur (Phase 1), low-risk BSIs require a period of reduced loading (Warden, Edwards & Willy, 2021). Bone remodelling then occurs via the activity of bone-resorbing osteoclasts to remove damaged bone, with osteoblasts forming new bone (Burr, 2002). Eriksen (2010) states "that osteoclast activation and resorption in cortical bone takes approximately 4 weeks, with 3 months being required to replace this with new bone, and up to a year required for full mineralization". Bone remodelling duration is also reported to be longer in trabecular bone versus cortical bone.

Image demonstrating both cortical and trabecular bone sites, along with osteoclast (bone resorbing) and osteoblast (bone forming) cell activity following a bone stress injury. Image from Scheuren et al (2017).

Although we need to respect bone healing timeframes, rehabilitation is primarily criteria-driven, not time-driven. This means that you will work towards meeting specific targets in each phase. If you don't put in the work in one phase, you will not be ready or able to move to the next. This process is proven to work and it ensures that we leave no stone unturned & that nothing gets missed during your rehabilitation. Thankfully, you may be able to cross-train in the early stages of rehab, along with completing exercises targeted at muscles away from the injured bone site.

Ultimately, the goal of rehab is not only to be back running or playing sport in a few weeks or months time, but to still be playing sport with healthy bones in 5 and 10 years time. Re-injury rates following stress fractures are high. With this in mind, I have refined my rehab process over the past 15 years, to ensure that you receive the latest evidence-based treatment & high quality exercise prescription.

Risk Factor Identification & Management Strategies

Identifying risk factors is crucial for preventing bone stress injuries. Risk factors are categorised as either intrinsic or extrinsic. Risk factors include:

Previous history of stress reaction / fracture

High running volume

Low energy availability (with or without an eating disorder)

Low bone mineral density or osteoporosis

Low body mass index

Delayed menarche or menstrual dysfunction

The table below outlines the most common factors that can contribute to the development of a bone stress injury, along with the optimal management strategy for each. Following a bone stress injury, failure to address any factors relevant to you, may lead to an unsuccessful return to sport or re-injury.

Human bones consist of a combination of both cortical and trabecular bone (Pathria, Chung & Resnick 2016). BSI risk factors can differ according to their anatomical location and relative bone composition, i.e. trabecular-rich versus cortical-rich bones (Temforde et al, 2022). For example, a study by Temforde et al (2022) of female college athletes, found that low bone mass density (BMD), low body mass index (BMI) and low weight were significantly more related to trabecular-rich bone stress injuries. Examples of trabecular-rich sites include the femoral neck, pelvis and the calcaneus (heel bone).

Planning Your Return To Running

The anatomical location of your bone stress injury will influence both your return to sport timeline and the risk of complication (e.g. non-union) (Hoenig et al, 2023). The table below outlines the approximate return to sport timeframes for the various types of BSI.

Image from : https://www.instagram.com/p/DGDdwEQMyRM/. Adapted from Hoenig et al (2023)

To successfully return to running after a bone stress injury, consider the following steps:

Follow a structured rehabilitation programme

Gradually increase running volume and intensity

Incorporate cross-training to maintain fitness

Monitor for any signs of pain or discomfort

A structured rehab programme at Buan Physio will include a number of mesocycles (e.g. 4-week blocks), with one example provided in the table below. Providing an athlete with a structured but adaptable plan such as this, allows for a smooth transition back to running.

An example of a 4-week mesocycle at Buan Physio, demonstrating an athlete's transition to their walk : run programme.

When Can I Start Running?

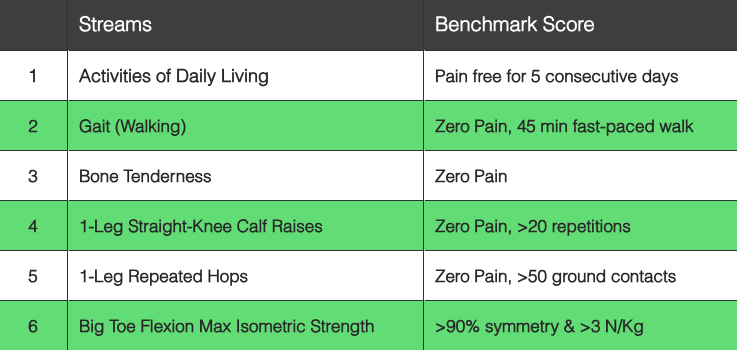

The bottom line is that passing your specific 'return to sport criteria' is the safest and most effective way to ensure a successful return to sport. Skipping phases or performing exercises sub-optimally will likely lead to issues arising when you start to run again. In order to offer context, the subsequent criteria (see table below) provides an example of the evaluation parameters utilised to determine an individual's eligibility to resume straight-line running following a bone stress injury.

* >90% symmetry means that there cannot be any more than a 10% difference between sides on testing.

Pain & Running Following a BSI

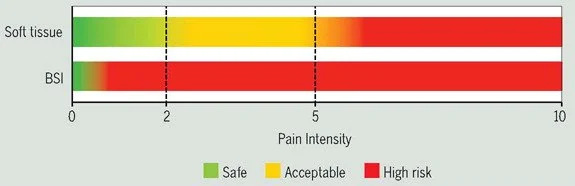

Unlike a soft tissue injury where it is deemed acceptable for an individual to experience a low level of pain (e.g. 0-3/10) whilst running, when managing BSIs there MUST be zero pain during a run, after a run and the following day. Image from Warden, Edwards & Willey (2021).

First of all, you will not have ran in at least 6 weeks in order to allow bone healing to occur (this may be longer depending on various factors). Once you have passed your specific return to running criteria, you will commence a walk : run programme. This programme will progressively build towards completing 5km runs again. Your running volume should be progressed before your running speed, as Edwards et al (2010) reported that "running the same distance but with decreased speed, from 3.5 to 2.5 m/s, reduced tibial BSI likelihood by half". Therefore, you will run at slower speeds initially.

Adequate recovery time between sessions (i.e. 48-72 hours) is also key in these early stages to ensure that the bone is managing the running loads. Subsequent running programme are then prescribed specific to your sporting demands

“Unlike a soft tissue injury where it is deemed acceptable for an individual to experience a low level of pain (e.g. 0-3/10) whilst running, when managing bone stress injuries there must be zero pain during a run, after a run and the following day.”

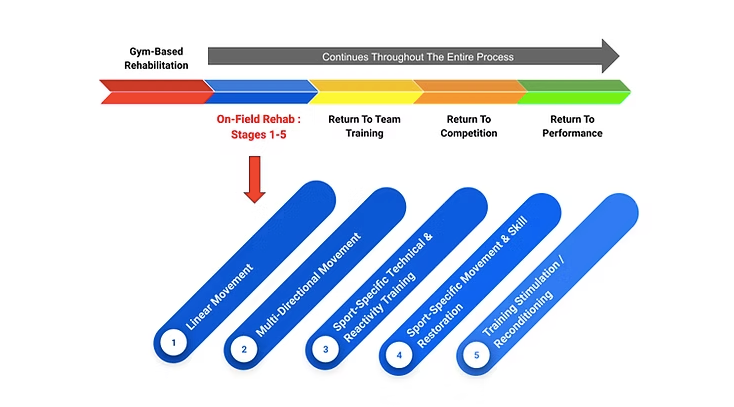

Team Sport Athletes : On-Field / On-Court Rehab

On-Field / On-Court Rehabilitation Pathway

For athletes involved in team sports, your on-field or on-court rehabilitation commences during phase 4. Decelerations, accelerations, change of direction speed and high speed running are all introduced over a number of weeks. Drills that are pre-planned in nature initially, progress to more reactive chaotic representative tasks as you progress through the 5 stages of OFR. Drills will begin to incorporate the use of the ball, in addition to engaging in contact work. The quality of movement throughout all 5 OFR stages is paramount, with both video analysis and a coaching eye employed to ensure this objective. Ultimately, stage 5 OFR sessions should bear a strong resemblance to a team training session.

Conclusion

Bone stress injuries are a common lower limb injury, especially among female athletes. Early detection is crucial for effective bone healing and a faster return to sports. MRI is the most sensitive and specific imaging method for diagnosing bone stress injuries, with fracture severity classified as either low or high risk. The location of the injury will affect the timeline for returning to sports. Once the specific criteria for resuming running are met, a walk-run program can be initiated. Following a structured yet flexible rehabilitation plan facilitates a smooth transition back to running. Finally, it is essential to address any modifiable risk factors that contributed to the injury, such as inappropriate training loads, inadequate recovery, low energy availability, menstrual cycle dysfunction, bone health issues, Vitamin D & Calcium deficiencies, and deficits in strength and control.

As a sports physiotherapist and strength and conditioning coach, my primary objective is to guide individuals safely and comprehensively through the rehabilitation process, ensuring a successful return to sports. I am convinced that this is best accomplished through a flexible, systems-based approach, where regular objective testing informs decision-making. For those in need of comprehensive rehabilitation following a bone stress injury, with meticulous attention to detail, Buan Physio is here to support your journey back to sports.

Success Stories

Femoral Neck Stress Fracture

"I went to see Declan thinking I had pulled a muscle in my thigh/hip. He put me through various exercises and questions about my injury - he quickly came to a conclusion suggesting I get a mri to rule out stress fracture on my hip. I was very surprised at his suggestion but did what he asked…. Stress Fracture confirmed! My orthopaedic consultant was very impressed with his quick diagnosis. After Four months of physio with Declan I’m back playing golf and gym three times a week. Thanks Declan my highest recommendation to you." Fiona

Hip Avulsion Fracture

"Declan Hardy was recommended to me by a friend. My son had a hip avulsion fracture from sports. Declan worked with my son and he did specific strengthening exercises, on-field rehabilitation, among other things. My son and I were really pleased with these treatments as they helped his pain and discomfort a lot over time. I would highly recommend Declan if you are in need of a physiotherapist who is an active listener, he truly cares about his patients and wants the best for them." Mirela

References

Burr DB. and Targeted and nontargeted remodeling. Bone. 2002; 30: 2– 4.

Derrick TR, , Edwards WB, , Fellin RE, , Seay JF. and An integrative modeling approach for the efficient estimation of cross sectional tibial stresses during locomotion. J Biomech. 2016; 49: 429– 435.

Edwards WB, , Taylor D, , Rudolphi TJ, , Gillette JC, , Derrick TR. and Effects of running speed on a probabilistic stress fracture model. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2010; 25: 372– 377.

Eriksen EF. and Cellular mechanisms of bone remodeling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010; 11: 219– 227

Fredericson M, Bergman AG, Hoffman KL, Dillingham MS. Tibial stress reaction in runners: correlation of clinical symptoms and scintigraphy with a new magnetic resonance imaging grading system. Am J Sports Med 1995; 23:472–481

Hoenig, T., Eissele, J., Strahl, A., Popp, K. L., Stürznickel, J., Ackerman, K. E., Hollander, K., Warden, S. J., Frosch, K. H., Tenforde, A. S., & Rolvien, T. (2023). Return to sport following low-risk and high-risk bone stress injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine, 57(7), 427–432.

Hutson, M.J., O’Donnell, E., Petherick, E., Brooke-Wavell, K., Blagrove, R.C., 2021. Incidence of bone stress injury is greater in competitive female distance runners with menstrual disturbances independent of participation in plyometric training. Journal of Sports Sciences 39, 2558–2566

Kijowski, R., Choi, J., Shinki, K., Del Rio, A. M., & De Smet, A. (2012). Validation of MRI classification system for tibial stress injuries. AJR. American journal of roentgenology, 198(4), 878–884. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.11.6826

Pathria MN, Chung CB, Resnick DL. Acute and stress-related injuries of bone and cartilage: pertinent anatomy, basic biomechanics, and imaging perspective. Radiology. 2016;280(1):21-38.

Robertson, G; Wood, A. (2017). Lower limb stress fractures in sport: Optimising their management and outcome. World J Orthop. 18; 8(3): 242-255

Scheuren, A., Wehrle, E., Flohr, F., & Müller, R. (2017). Bone mechanobiology in mice: toward single-cell in vivo mechanomics. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology, 16(6), 2017–2034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10237-017-0935-1